Adnexal masses are one of the most common gynecological diseases. Its prevalence is estimated to be 5-10% in women of reproductive age (1). Minimally invasive surgery (MIC) is the gold standard in benign adnexal masses. MIC is associated with faster recovery, less pain, less hospitalization time and better cosmetic results (2). However, MIC has some limitations in adnexal masses; the first trocar entry is difficult due to the mass, the space-occupying effect of the mass restricts intra-abdominal exploration, and there is a risk of rupture that may develop during all these stages. Intraoperative rupture does not cause problems in benign masses. But the rupture of suspicious masses can cause malignant cells to spread to the abdomen in the pneumoperitoneum environment, and this is undesirable.

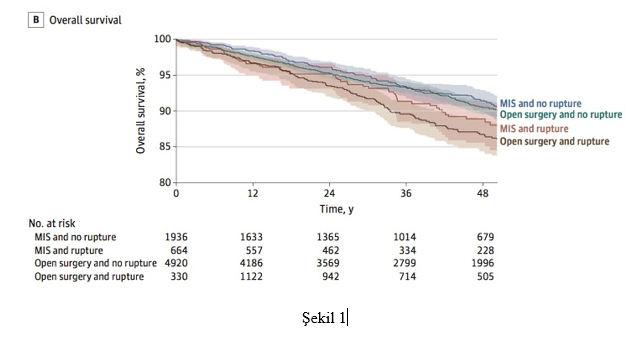

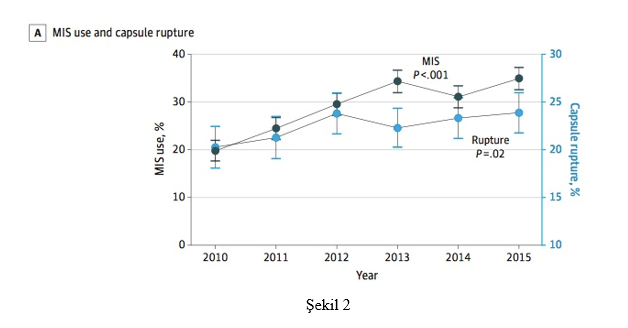

What is the probability that suspicious and malignant masses will rupture during MIC?Intraoperative rupture causes the disease to skip the stage and increase to Stage 1C1 in early stage ovarian cancer. As a result, it also leads to the patient receiving adjuvant chemotherapy and exposure to unnecessary chemotoxicity. For this reason, it is essential to avoid rupture in all suspected adnexal masses. In a current study conducted with the National Cancer Database data in the United States, the rate of MIC use in early stage ovarian cancer increased from 19.8% in 2010 to 34.9% in 2015 (3). This increase in MIC use was reflected in the intraoperative rupture rate and increased from 20.3% to 23.9% during the same period. While the 4-year survival rate was 91.5% in patients without rupture in MIC, this rate decreased to 88.9% in intraoperative ruptures. In other words, in the event of a rupture, there is a 2.6% loss of survival in patients. In the same study, intraoperative rupture cases were also observed in the open surgery group (21.3%) and reduced 4-year survival from 90.5% to 86.8% (Figure 1). Intraoperative rupture is not only a complication specific to MIC and is also observed in laparotomy (25.5% MIC vs 21.3% LT, aRR:1.17), but this difference against MIC is statistically significant (Figure 2). In the same study, it was found that large masses also increase the risk of intraoperative rupture.

Is the prognosis affected if an intraoperative rupture develops in early stage ovarian cancer?

Is the prognosis affected if an intraoperative rupture develops in early stage ovarian cancer?

A retrospective study conducted in Japan examined 15,163 Stage 1 ovarian cancers and identified 7,227 cases of iatrogenic (intraoperative rupture). In the study, it was found that intraoperative tumor rupture is most common in Clear cell cancer (4). While ruptures that develop in clear cell cancer negatively affect the prognosis, the prognosis was not negatively affected in ruptures that develop in other types of cancer. The same study revealed that in all histological types, adjuvant chemotherapy administered due to intraoperative rupture (Stage 1C1S) does not make a positive contribution to the prognosis. However, the NCCN guidelines recommend applying adjuvant chemotherapy to the Stage 1C group (1C1, 1C2, 1C3) without distinction between subgroups (5)

Can intraoperative rupture of suspected adnexal masses be prevented in MIC?Adnexal mass rupture in MIC can occur in 3 stages. The first is the entrance stage to the west. Ultrasound or other imaging methods (CT, MRI) should be used to determine whether the adnexal mass is attached to the abdominal wall and how far it extends proximally. A safe point should be determined between the umbilicus and the xyphoid, on the Decline, so that the first trocar entry should be made.

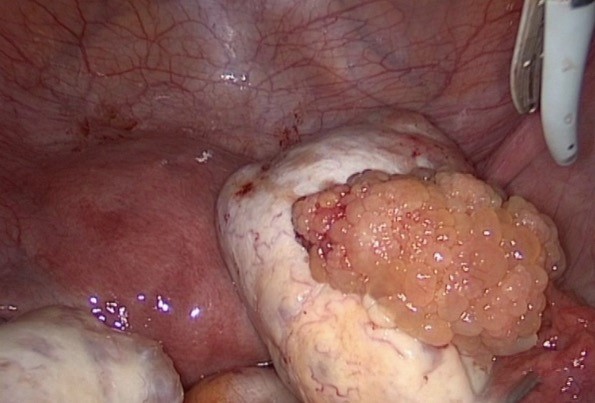

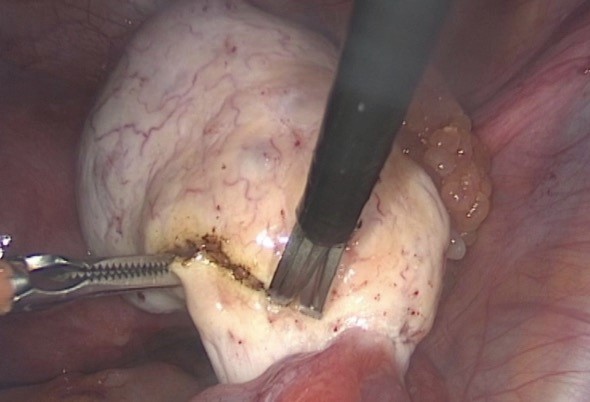

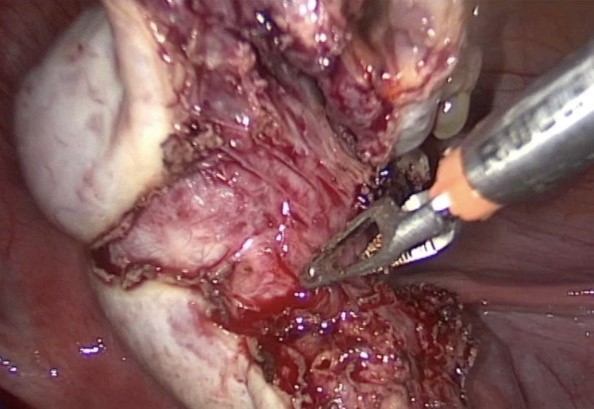

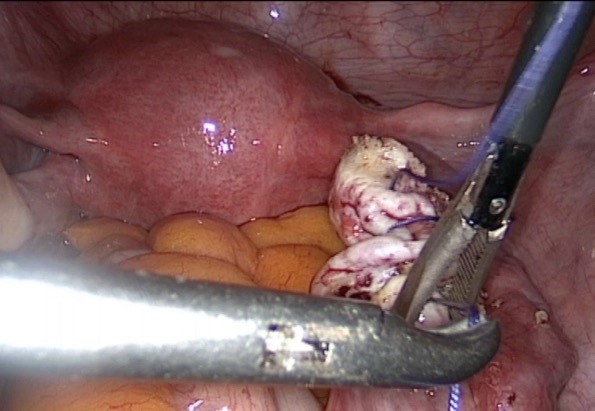

The second risky stage occurs during the manipulation of the adnexal mass in the abdomen. The risk of rupture during cystectomy is higher than salpingo-oophorectomy. For this reason, it is more rational to avoid cystectomy and perform USO if the suspected mass has developed from a single adnexa in patients without fertility expectations. In cases where cystectomy should be performed (bilateral tumor, fertility expectation), instead of classical cystectomy; the normal ovarian tissue limit should be determined and wedge resection should be performed on the mass by sacrificing a small amount of healthy tissue, thus avoiding rupture of the suspicious mass (Figure 1,2,3,4).

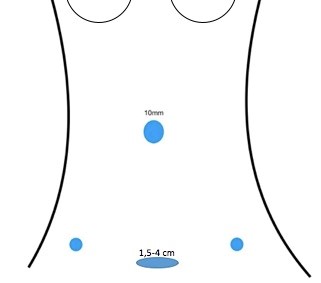

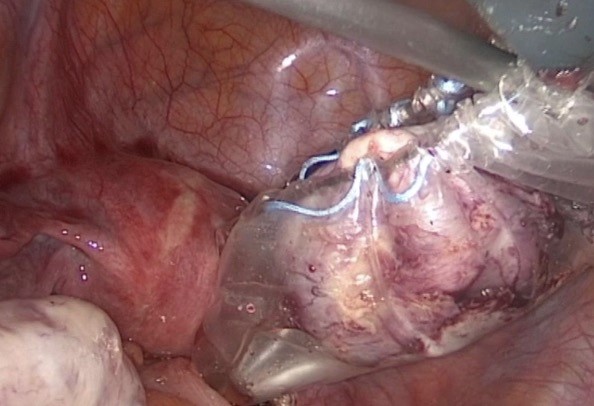

The third risky stage is the removal of the suspicious mass out of the abdomen. For suspicious masses, an endobag larger than the mass size should always be used. In addition, it should be determined in advance where the mass will be removed. In cases where hysterectomy is performed, sending the endobag vaginally is the most appropriate approach. In sexually active women, incisions made to the posterior fornix of the vagina can also be used by protecting the uterus. If the abdominal wall is to be used, the most suitable area is mini-pfannenstiel (1.5-4 cm) incisions to be made through 2 fingers of the pubic arch (Figure 3). In every 3 ways, the bag should be mouthed to the outside, the cyst content should be aspirated or morseled and the mass should be taken out. Even the best quality bag will tear if pulled with excessive force. For this reason, it should be avoided to try to remove the mass with the bag. While the mass is being taken out, whether the bag is intact should be monitored with a camera (Figure 5,6,7).

Patient selection is one of the most important stages for MIC. It should be borne in mind that infectious processes can mimic malignancy, and the presence of abscesses should be excluded. In addition, subserous fibroids, retroperitoneal masses, small bowel tumors, and appendix tumors can also mimic adnexal masses. In the presence of a suspicious adnexal mass, the entire abdomen should be evaluated by CT or MRI and whether there is a peritoneal, parenchymal or lymph node metastasis should be investigated. It is important not to be satisfied with the radiology report and that the images are also evaluated by the surgeon who will perform the surgery. The size of the mass should be measured and it should be confirmed that there is an endobag of the appropriate diameter in the operating room. The “Visceral Sliding” test can be used to make the entrance to the abdomen safe (6). This test is a simple, inexpensive and fast learning curve test and also helps to recognize intra-abdominal adhesions. In addition, whether the patient can tolerate the pneumoperitoneum and trendelenburg position should be evaluated together with the anesthesiologist. After all these stages, the decision to start with MIC can be made.

The decision to finish with MICAfter entering the abdomen with a laparoscope, the entire abdomen should be evaluated; whether the adnexal mass adheres to the surrounding tissue, whether there is a capsule invasion, the condition of the opposite ovary and the presence of peritoneal metastases should be noted. At this “diagnostic” stage, a decision should be made whether the operation can be completed with MIC. If the mass can be removed without rupture and if the frozen result is malignant, the other stages of the operation can also be completed with MIC, a continuation decision can be made. Otherwise, it is necessary to proceed to laparotomy with a vertical incision.

ResultThe NCCN guideline recommends the use of MIC in early stage ovarian cancer only in selected patients and provided that it is applied by experienced surgeons (5). MIC is only useful when there is no rupture and staging surgery can be performed completely. Every surgeon who performs MIC should prioritize patient safety and strictly adhere to oncological principles.

References